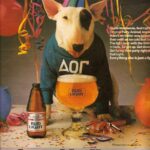

In the whirlwind of 1980s pop culture, few advertising mascots burned brighter—or more bizarrely—than Spuds MacKenzie. Introduced by Anheuser-Busch in 1987 to promote Bud Light, Spuds was an English bull terrier with a laid-back demeanor, a surf-party vibe, and a Hollywood agent’s charisma. Within months, he was on TV, in magazines, on posters, T-shirts, beach towels, and even lunchboxes. He became a pop culture icon almost overnight. But he was also the center of controversy, marketing debates, and the era’s evolving conversation about the ethics of advertising—especially when it came to selling beer using what looked suspiciously like a children’s cartoon character. Spuds MacKenzie wasn’t just a dog. He was a symbol of the 1980s—flashy, excessive, and just a little bit wild.

In the whirlwind of 1980s pop culture, few advertising mascots burned brighter—or more bizarrely—than Spuds MacKenzie. Introduced by Anheuser-Busch in 1987 to promote Bud Light, Spuds was an English bull terrier with a laid-back demeanor, a surf-party vibe, and a Hollywood agent’s charisma. Within months, he was on TV, in magazines, on posters, T-shirts, beach towels, and even lunchboxes. He became a pop culture icon almost overnight. But he was also the center of controversy, marketing debates, and the era’s evolving conversation about the ethics of advertising—especially when it came to selling beer using what looked suspiciously like a children’s cartoon character. Spuds MacKenzie wasn’t just a dog. He was a symbol of the 1980s—flashy, excessive, and just a little bit wild.

The first appearance of Spuds MacKenzie came during the Super Bowl XXI broadcast in January 1987. The commercial was unforgettable: beach parties, bikini-clad women, and Spuds, cool as ever, rocking shades and surrounded by adoring fans. The premise was absurd—a party dog who everyone wanted to hang out with—but it worked. America fell in love with the pooch. Within days, Anheuser-Busch knew they had struck marketing gold. By the end of 1987, Spuds was the face of Bud Light, featured in a massive merchandising blitz that included everything from keychains to plush dolls.

The brilliance of the campaign was rooted in its contradiction: Spuds didn’t drink beer. He didn’t speak. He didn’t bark orders or flash a brand name in your face. He just was. And yet, his presence was so strong—so effortlessly “cool”—that he became the face of a lifestyle. Bud Light wasn’t just a beverage anymore; it was a ticket to the good life, where everyone was having fun, the sun was always out, and the party never stopped. And Spuds MacKenzie was the VIP guest of honor.

Part of Spuds’ appeal came from the fact that he was completely unexpected. Most mascots in advertising were cartoon animals or abstract characters. Spuds, though stylized, was a real dog. And not just any dog—he had a unique look that was both awkward and charming, with his squat build, pointy ears, and distinctive patch over one eye. He wore Hawaiian shirts, played the drums, lounged by pools, surfed, and was often surrounded by a crew of scantily clad women referred to as the “Spudettes.” This wasn’t subtle branding—it was the marketing equivalent of blasting hair metal from a boombox on a yacht.

The dog behind the sunglasses was actually a female bull terrier named Honey Tree Evil Eye, or “Evie” for short. She was trained in California and became a celebrity in her own right, although her identity as a female was kept quiet to maintain the masculine persona of Spuds. The character quickly transcended beer commercials. He was everywhere. Late-night TV mentioned him. SNL parodied him. Kids wore Spuds shirts to school (which, in some cases, led to those shirts being banned). Adults threw Spuds-themed parties. He even appeared on magazine covers. For a dog that didn’t say a word, Spuds MacKenzie had serious cultural clout.

But with all this attention came controversy. Almost immediately, watchdog groups began questioning the ethics of using a cartoonish dog to promote alcohol. Critics argued that Spuds appealed too much to children—that his presence blurred the line between adult products and kid-friendly imagery. The mascot looked more like a Saturday morning cartoon character than a beer pitchman. And as the Spuds merchandise spread—into toys, posters, and schoolyards—the line kept getting fuzzier.

The federal government took notice, as did advocacy groups like Mothers Against Drunk Driving. Congressional hearings were held. Bud Light insisted that Spuds was aimed squarely at legal drinkers and was never intended for children. But the backlash grew, especially as studies began to suggest that children recognized Spuds MacKenzie more readily than they did Ronald Reagan or Mickey Mouse. That was a problem. In an era increasingly conscious of media influence and the effects of advertising on youth, Spuds became a lightning rod for criticism.

Anheuser-Busch eventually relented. In 1989, after only two years on the job, Spuds MacKenzie was quietly retired. The official line was that the campaign had run its course, but insiders admitted that the growing scrutiny made it no longer worth the risk. The last Spuds ad aired during Super Bowl XXIII in 1989, ending one of the most flamboyant and fast-burning ad runs of the decade. Spuds disappeared as quickly as he arrived—but his legacy never truly left.

What makes Spuds MacKenzie such a fascinating character isn’t just the absurdity of a beer-hawking dog in a Hawaiian shirt. It’s what he represented. He was the embodiment of late-’80s excess—carefree, materialistic, image-obsessed. He sold not just a product, but an idea: that life was one long party, and if you were cool enough (or drank the right beer), you could join in. In many ways, Spuds was the animal cousin to other cultural avatars of the era, like Max Headroom or Gordon Gekko—a cartoonish exaggeration of success, fun, and popularity, pitched right into the heart of America’s consumer dream.

But unlike those other figures, Spuds was uniquely accessible. He wasn’t cynical or cruel. He didn’t talk. He just chilled. And in an era increasingly saturated with over-the-top marketing, his low-effort coolness stood out. That’s part of why he stuck in people’s memories. He wasn’t trying hard. He didn’t have to. He was Spuds.

Decades later, Spuds MacKenzie remains a symbol of a specific moment in time. He’s been referenced in pop culture, reappeared in ironic nostalgia ads (like the 2017 Super Bowl Bud Light commercial where he appeared as a ghost), and continues to be printed on retro t-shirts and novelty items. For many who lived through his heyday, he’s more than a marketing footnote—he’s a memory of a time when commercials were events, mascots could become celebrities, and a dog in sunglasses could sell millions of gallons of beer.

The rise and fall of Spuds MacKenzie tells us a lot about the 1980s: the unfiltered enthusiasm for branding, the fine line between advertising and entertainment, and the way public consciousness evolved when it came to targeting kids. It’s easy to laugh now at the absurdity of a beer company’s party dog becoming a cultural icon, but in a decade defined by neon colors, catchphrases, and pop culture saturation, Spuds fit right in.

He wasn’t just the life of the party—he was the party. And like many things from the 1980s, he came in fast, burned brightly, and vanished before overstaying his welcome. Spuds MacKenzie didn’t change the world, but for a little while, he made it a lot more interesting.