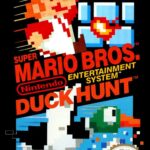

When the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) launched in North America in 1985, it wasn’t just a new video game console—it was a revival of the entire video game industry. Following the infamous crash of 1983, where cheap, low-quality games and oversaturation nearly killed consumer confidence, Nintendo emerged from the wreckage like a savior in gray plastic. But even more iconic than the console itself were the games that came bundled with it. For millions of kids, their introduction to the NES—and to video gaming as we know it—came in the form of a single cartridge: Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt. One game defined platforming for generations. The other turned your living room into a shooting gallery. Together, they became the ultimate package deal of the 1980s.

When the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) launched in North America in 1985, it wasn’t just a new video game console—it was a revival of the entire video game industry. Following the infamous crash of 1983, where cheap, low-quality games and oversaturation nearly killed consumer confidence, Nintendo emerged from the wreckage like a savior in gray plastic. But even more iconic than the console itself were the games that came bundled with it. For millions of kids, their introduction to the NES—and to video gaming as we know it—came in the form of a single cartridge: Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt. One game defined platforming for generations. The other turned your living room into a shooting gallery. Together, they became the ultimate package deal of the 1980s.

The Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt combo cartridge was everywhere. It was packed in with many NES systems, especially the Deluxe and Action Sets, and served as the foundation of millions of gaming memories. In a single gray cartridge, it offered two very different types of experiences. On one side, a meticulously crafted fantasy world full of bright colors, secret paths, and Goombas. On the other, a hunting simulation that let you aim a bright orange light gun at the screen and fire away at flapping ducks or clay pigeons. The games had almost nothing in common, yet their marriage on that single cartridge formed an indelible part of 1980s pop culture.

Let’s start with Super Mario Bros., the game that redefined platformers and arguably invented the modern side-scroller. Released in Japan in 1985 and bundled in with NES consoles in the U.S. shortly afterward, Super Mario Bros. featured a plumber named Mario (and optionally, his brother Luigi in two-player mode) on a quest to save Princess Toadstool from the evil Bowser. What seemed like a simple fairy tale setup became a revolutionary leap in game design. For many kids, this was their first taste of video game storytelling, even if that story was just “rescue the princess by stomping turtles and jumping over lava.”

But Super Mario Bros. was more than its plot—it was about feel, flow, and discovery. The first level, World 1-1, is often cited as a masterclass in intuitive game design. Without a single tutorial screen or pop-up window, it teaches the player everything they need to know: jump on enemies, hit question blocks, collect coins, and keep moving to the right. That first mushroom? It walks toward you menacingly, prompting a panicked jump. The next mushroom, a power-up, appears and moves in the same way, but when you grab it, Mario grows in size. It’s brilliant, wordless instruction.

And then came the warp pipes, the star man, the fire flower, the hidden 1-UPs, and the infinite loop of World 1-2’s warp zone. Every kid on the block knew some secret, some shortcut, some rumor about where to find a hidden block or how to skip entire worlds. Super Mario Bros. was a schoolyard legend. It was the type of game you didn’t just play—you talked about it, wrote about it, dreamed about it. Entire generations of kids shared strategies like sacred texts: “If you run and duck under that staircase in World 1-2…” or “If you jump just right on that turtle, you get infinite lives.”

The physics of the game were tight but forgiving, which made it both accessible to newcomers and rewarding for experienced players. The levels increased in difficulty but rarely felt unfair. They invited repetition. You played and died, played and died, but each time you got a little farther. You learned the rhythms. You memorized enemy patterns. You became better, not because of power-ups, but because of muscle memory and persistence. In the process, Super Mario Bros. planted a flag in your imagination.

On the same cartridge, however, was something completely different: Duck Hunt. In a sense, Duck Hunt was the arcade game brought home. It came bundled with the NES Zapper, a plastic light gun that looked like a sci-fi ray gun in Day-Glo orange. For a kid in 1987, this wasn’t a controller—it was a weapon. It turned your living room into a shooting range. The game itself was straightforward. Ducks flew across the screen one or two at a time, and your job was to aim the Zapper and shoot them out of the air before they escaped. A smug dog would jump out of the grass to retrieve your prize—or laugh mockingly if you missed.

That dog. That infernal dog. He didn’t say a word, but the way he popped up and chuckled with his hands on his belly became one of the most iconic and hated images in all of video games. Kids would hurl insults at the screen. Some even tried to shoot the dog in frustration. He was unkillable, but he was a perfect symbol of the stakes: miss the duck, get humiliated. Succeed, and bask in digital glory.

Duck Hunt used an innovative light-detection system that allowed the Zapper to “read” where you were aiming. When you pulled the trigger, the screen would briefly flash black with a white square where the duck was. If the photodiode in the Zapper detected that flash, it registered a hit. It was a clever and surprisingly reliable bit of technology—at least when played on old CRT televisions. It didn’t work on modern flat-screens, which is why Duck Hunt now lives primarily in memory and emulation.

While Duck Hunt lacked the expansive world of Super Mario Bros., it offered something else: pure, twitch-based fun. It was about reflexes and timing, not exploration. And like its cartridge sibling, it was designed for repeat play. It didn’t have an ending in the traditional sense—it just kept getting faster, harder, more relentless. Players were drawn into the hypnotic rhythm of ducks appearing, shots fired, scores tallied. In a sense, it was the spiritual cousin to classic arcade shooters, distilled into a home format.

The combined power of Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt made the NES more than just a console—it made it a gateway into two different types of gaming joy. For kids growing up in the ’80s, this cartridge wasn’t just a game—it was a summer vacation in plastic. It was Saturday mornings. It was sleepovers. It was shouting at the screen with your cousins. It was friendly arguments over who got to be Luigi, or who could get to World 8 without warping. It was the joy of pressing a plastic trigger and watching a duck fall from the sky. It was the first step into a lifelong relationship with video games.

The cultural impact of these two titles cannot be overstated. Super Mario Bros. would go on to spawn a franchise that remains central to gaming today. It’s the cornerstone of Nintendo’s legacy and continues to influence game design across the industry. Duck Hunt, while more of a relic, holds a special place in gaming history as one of the most successful light gun games ever made and an unforgettable part of the NES launch era. Together, they represented the versatility and innovation of the NES—a system that could deliver both sweeping adventure and arcade action in the same breath.

And maybe that’s what made the Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt cartridge so perfect. It captured the duality of what gaming was becoming in the 1980s. On one hand, a medium that could transport players to magical kingdoms filled with lava pits, mushroom kingdoms, and heroic quests. On the other, a source of pure, visceral fun that turned your living room into a shooting gallery. It was fantasy and sport. Storytelling and action. Challenge and reward. All of it packed into a gray cartridge with a tiny red label.

So for those who grew up in that golden era, the moment you slid that cartridge into the NES and heard the first few notes of the Super Mario Bros. theme, or heard the zap of the light gun charging up, it wasn’t just nostalgia. It was the sound of childhood itself. It was a portal to a world that felt infinite, whether you were jumping on Koopas or aiming for flying ducks. And it all started with two games, one console, and a little gray box that plugged into the front of your TV.